The following story contains spoilers for The Last of Us Season 1, Episode 1.

For all the successes that new-age streaming services like Netflix, Hulu, and Apple TV+ have had in recent years, it’s still hard to make the case that anyone else has found the key to consistently producing TV at the level of a good old fashioned HBO show. In the 2009 movie I Love You, Man, Paul Rudd asks Jason Segel a simple question over the phone: “Have you ever watched Sunday night programming on HBO? It’s spectacular.”

At the time, that was meant as a joke to show Rudd’s character as someone bubbled into a specific life routine. But 14 years, a whole bunch of TV, and a general dispositional shift to where it now seems like many prefer staying home and watching TV, and guess what: HBO programming remains spectacular.

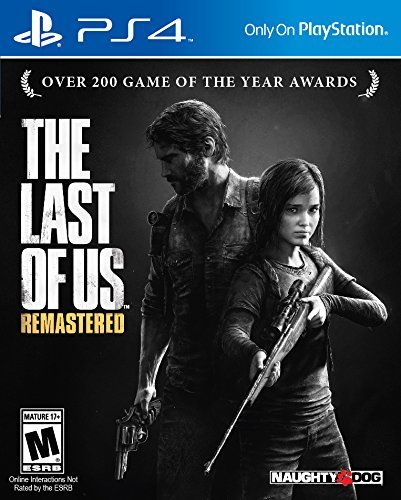

The premium cable network’s latest big swing at dominating the small screen conversation comes in the form of The Last of Us, an adaptation of the beloved 2013 survival horror video game. They’ve reportedly spent as much as $100 million on the show’s first season, according to a piece in The New Yorker, and have put full trust in the hands of a pair of capable creators: Neil Druckmann, the game’s writer/director, and Craig Mazin, who was behind one of the network’s most successful limited series ever, Chernobyl.

The Last of Us is HBO going big game hunting; it aims to be HBO’s next epic genre smash, something that can only be compared to massive successes (like Game of Thrones or Watchmen) or relative flops (the later seasons of Westworld or Lovecraft Country). The show is set, technically, in our present year of 2023, but the reality is something closer to Mad Max, Station Eleven, or Children of Men; this isn’t a recognizable present—it’s one decimated by a pandemic and sickness that society had no proper response to.

The show, which stars Pedro Pascal and Bella Ramsey in its lead roles, closely follows the plot of the game; I know this personally, because I played the game exactly once. And while I remember the little I played of the game vividly—I liked it quite a bit—it was in the back end of my gaming days. Many reviewing and writing about The Last of Us will likely have experience as someone to whom the games are of great importance and mean a lot; I’m just someone familiar and looking for a great horror/sci-fi story.

And in the early goings, that seems to be what The Last of Us is. The show moves through time periods and settings with a brisk pace, and if the opening credits tell you anything, the only consistent cast members throughout will be Pascal and Ramsey. And for anyone familiar with either of their work, it should come as no surprise that both are up to the task to engage with the moments of action and attacks, yes, but also the emotional turmoil quiet intensity that can come in between.

Pascal is best known at this point as the man under the mask in The Mandalorian, but he’s been on a hot streak for almost a decade. From his wonderful single-season arc on Thrones, to last year’s meta-farce action comedy The Unbearable Weight of Massive Talent, to even a good turn in a bad Judd Apatow comedy, The Bubble, it’s clear that Pedro Pascal has the juice. Ramsey (who uses both she/her and they/them pronouns), too, has built up an impressive resume of her own; she stole the show in her own Thrones arc as Lady Lyanna Mormont, but also impressively led Lena Dunham’s Catherine Called Birdy feature film last year.

While the characters surrounding those two are constantly shifting—much of the first episode is, in fact, from someone else’s POV—these are the performers putting The Last of Us on their back, and who, along with Mazin and Druckmann, are responsible for determining whether this will eventually reach the high heights of Thrones or Watchmen, or just be another genre show for HBO’s impressive back catalogue.

So far, after an 80-minute debut, it’s on the right track. Let’s talk about the first episode of The Last of Us.

1968

The show kicks off with a cold open set in 1968, depicting a scene from a talk show interview (hosted by an intellectual played by Silicon Valley’s Josh Brener) with a pair of scientists. One has little alarm for the future, but the other is worried of a specific kind of pandemic and infection: fungal.

He describes, in great detail (and sets the tone for viewers in an easy-to-understand way) the exact kind of pandemic he fears: a fungus that infects, deranges, and, eventually, takes over a body from the inside out. This wouldn’t be possible, of course, due to the temperature of the human body, which wouldn’t be able to house such a fungal infection.

But, he adds, if the earth were to get just a tiny bit warmer, things could change. At that moment, you may as well start playing the John Williams theme from Jaws. As he describes the nightmare that Chekhov’s Climate Change will eventually bring on, the audience grows quieter and quieter; there’s no rebuttal to what he says. Even in 1968, the reaction is a resounding well, we’d really be fucked then.

Worth noting, too, that the 1968 setting for this opening scene cannot possible be an accident. 1968 was the first documented year of governing bodies learning of the potential effects of climate change. The Last of Us is a horror story, but one rooted in a horror we truly find ourselves in.

1968 also marked the year that George A. Romero’s debut zombie film Night of the Living Dead was released. Without that movie and all that it inspired in the subsequent decades, The Last of Us would not exist; our existential anxieties simply would have had to develop elsewhere.

2003

We then pick up in 2003—the moment, presumably, in TV’s The Last of Us universe where the earth got just warm enough for the fungal pandemic warned of in 1968 to begin to hit. It’s also the year when everything else stopped; after a time jump later in the episode, a Gore/Lieberman shirt (from the 2000 U.S. presidential election) hammers this point home. You don’t see too many of those in our 2023.

Mazin, who directs the first episode, introduces us to both Joel (Pascal) and his daughter, Sarah (Nico Parker); he follows the interesting decision the the game makes, however, to keep the entirety of this portion of the episode in Sarah’s POV. The episode’s coloring feels like a warm fall day, and it doesn’t take much to feel some real father-daughter chemistry between Pascal and Parker.

The day in question—the last day, as it turns out—is Joel’s birthday, but he doesn’t seem to care all too much, outside of it being an excuse to spend time and make memories with his daughter. Sarah is much more excited about it than he is, using the day as an excuse to get his prized watch fixed, and nagging her dad to get a cake for his birthday; we don’t know the exact nature of their history, but it’s clear that a mother is no longer in the picture and it’s drawn them close together. Sarah in particular is eager to create more lasting memories with her father.

The early portion of the episode is light on plot, but heavy on characterization. Sarah has a lazy day, hopping on a bus as soon as her school day ends to secretly get her father’s watch fixed for his birthday, while Joel is off working jobs as a contractor; his brother, Tommy (Gabriel Luna) is also around and clearly the loose cannon of this family dynamic. We also get our first sense of impending doom through Sarah’s eyes; there’s an increasingly present military presence every time she turns her head, and things hit a point of no return when she’s getting the watch fixed and the store owner’s wife quickly shoos her out. Something is off.

When she returns home, she stops next door to say bake some cookies with Ms. Adler, the wife of the couple next door whose sick and elderly mother lives with her. In perhaps the most unsettling moment of the episode—an episode filled with violence, sickness, and attacks!—we see Mrs. Adler’s mother go through some sort of transformation in the background, out of focus; Sarah doesn’t notice, but still seems to sense something’s off.

Sarah and Joel get to celebrate his birthday; she gives him his fixed watch, but he forgot to get himself a cake, much to her dismay. And then he has to head out to help Tommy, who’s gotten in trouble. Sarah heads to bed, and Joel heads out. Not the most storybook 36th birthday for Joel.

Things hit the fan when Sarah is awoken in the middle of the night to loud noises and the emergency broadcast system on TV. She goes next door to see the Adlers both dead, big bites taken out of them by Mrs. Adler’s mother, who’s got living fungus bursting out of her mouth. Sarah gets outside and just as the old woman is about to make her into her next meal, Joel pulls up with his brother in tow, saving Sarah, and killing Mrs. Adler’s infected mother—his first of many likely killings to come.

As Sarah, Joel, and Tommy attempt to get as far away as possible—it’s said that most of this mystery sickness is coming from the densely populated city—they scramble through the road just as everyone else does. One scene, driving through a small town with people, some infected and some not, around them, feels like a cut scene straight out of the game, all still from Sarah’s perspective in the back seat.

The final scene of the 2003 vision is a heartbreaker; as the military enforcement finds them, Joel makes it clear: they are not sick. But the soldier fires regardless before being taken out by Tommy. Joel—who was holding Sarah in his arms due to an ankle injury she sustained—survives, but Sarah is hit. Pascal is heartbreaking in this moment, one that likely stunted Joel for decades.

It’s worth noting that when a deadly, unknown sickness is rampantly hitting mankind, it’s still a person—a bullet—that kills Sarah. A red herring earlier, in the car, leaves us thinking that maybe Sarah could be infected; she was by Mrs. Adler’s sick mother and has no idea how contagious this thing could be. But The Last of Us isn’t playing around: mankind will always be the biggest detriment to mankind, even in the apocalypse.

2023

We flash forward two decades to our now post-apocalyptic world, Boston in particular. The warm, fall feeling of 2003 is exchanged for a cold, drowned coloring of an unrecognizable 2023. A camp has been set up by FEDRA, the disaster relief agency, where soldiers keep order; we constantly hear of the Fireflies, a rebel group actively against FEDRA, whose main political strategy seems to be “blow things up.”

Now older and clearly rougher around the edges, Joel, has become a smuggler who helps people get pills, weapons, or anything else their hearts might desire (Pascal doesn’t look that much older, but his now salt and pepper hair does enough).

Joel never takes off the watch Sarah got fixed for him, still damaged by a bullet from that fateful night in 2003, representing the exact moment that his daughter died. By choosing not to take that watch off, we see that, whether a conscious or unconscious choice, he’s unable to move on.

Nonetheless, Joel has also since found himself a life partner. We meet Tess (played by Fringe and Mindhunter‘s Anna Torv, always a pleasure) as she’s just been ripped off by a dude named Robert and his band of thugs (even at the end of the world, groups up to no good have emerged and will continue to emerge). Sarah was trying to get a car battery so that Joel could power his car up to go find Tommy, who surprisingly is still alive but unsurprisingly has gone missing. After an explosion takes several of the guys in the room out, she heads back.

This is also where we meet Ellie (Ramsey), who’s being held captive by the Fireflies and their leader, Marlene (a stern Merle Dandridge), for a reason that’s not initially clear. Ellie is spunky; she curses at her captors, and doesn’t seem to really have any home or direction. Mazin’s writing tells us in subtle and smart ways what’s so special about Ellie: she’s been infected, but she’s not sick. She hasn’t transformed. She’s a “2023” medical miracle.

Which, then, brings us to the union of Joel and Tess with Ellie. Marlene was going to bring Ellie out west herself, eager to see what science can become of her condition; a run in with that douchebag Robert left him dead and Marlene and her closest lieutenant quite injured. The Fireflies offer Ellie up to Joel as yet another smuggling job: if they get her where she needs to go so she can be studied, they can have the car battery, and hopefuuly find Tommy on the way. Joel is kind of over it, but Tess convinces him to get on board—it’s the only option.

As Joel and Tess take Ellie in, she sees their home, and their station for signaling from smuggler friends Bill and Frank, whom we will surely meet in future episodes: an encyclopedic book of hit songs, organized by year, is the basis of the code they’ve set up. ’60s song means nothing new; ’70s means something’s in; and while ’80s isn’t initially clear, Ellie is sharp enough to coax Joel into figuring it out.

It’s clear even from the early goings that the relationship between Joel and Ellie is likely to mirror the storytelling trope of the reluctant guardian; we’ve seen this in recent years with Pascal’s other TV blockbuster role in The Mandalorian, but perhaps even closer to the Joel/Ellie dynamic could be the Hopper/Eleven dynamic from Stranger Things—another father/daughter surrogate relationship motivated, in part, by loss.

Throughout the course of The Last of Us, Joel has a number of moral decisions that he will presumably have to make. The first came in the 2003 portion of the episode, when he opted not to help a family with a child alongside the road as he, Sarah, and Tommy were first escaping. The next comes at the end of the episode as they are smuggling Ellie out of the military zone. Joel and Tess run into the same soldier who Joel sold pills to earlier in the episode; this brings us to the best moment of the episode.

Joel, at this point, doesn’t even know Ellie. But when faced with a situation that mirrored one that cost his daughter’s life, he acts instinctually. Last time, his daughter was physically in front of him—just due to his holding her during his injury. That decision cost Sarah her life. When the soldier is pointing his gun at Joel and Ellie, Joel lunges forward, coming at the soldier with 20 years of pent up rage. It’s another piece of this great moment to see as Ellie’s deranged initial joy at the sight of Joel’s violence turn into something of a resigned fear. Joel gets up and moves on with his life; the soldier does not.

Our heroes continue their journey on the road, and the camera then cuts back to Joel’s radio just as “Never Let Me Down Again” by Depeche Mode begins to play. ’80s song. Mazin and Druckmann put it on us to figure out—but we can already assume that it means trouble from Joel’s smuggler friends.

It’s fun to find a hero at the start of the story as fed up as Joel already is. Throughout the episode, we see a refrain painted on walls: “When you’re lost in the darkness, look for the light.” It’s clearly a rallying cry, probably from the Fireflies, that some people use to motivate themselves through these dark times.

It reminds me a bit of the later seasons of Lost, when Jack (Matthew Fox) would repeatedly say “If we can’t live together, we’re going to die alone.” It was a line so often repeated, that at a certain point it just became an empty platitude, and Rose (L. Scott Caldwell) told him as much. When one random guy starts saying “When you’re lost in the darkness…” to Joel, he shuts him up right away. He’s already there. He’s already tired. And this is a great look into our lead character’s frustrated headspace.

So ends an absolutely jam-packed first episode of The Last of Us. And it’s clear already that the show is going to live and die by the combination of Pascal and Ramsey along with the way Mazin and Druckmann choose to bring this all to screen.

Evan is the culture editor for Men’s Health, with bylines in The New York Times, MTV News, Brooklyn Magazine, and VICE. He loves weird movies, watches too much TV, and listens to music more often than he doesn’t.